MachAInst: Digital Score for inclusive music education for disabled children in Kenya.

Developing a digital score as a platform for inclusive music education for disabled children in Kenya. The digital score was embedded with a learning game, and a low-cost digital instrument interface that break barriers of accessibility to music education and making, while building bridges towards inclusive music-making and learning.

The Issue

In many cultures around the world being a disabled child means being segregated: different schools, different opportunities, different funding, different access. In music education that can involve having limited access to instruments and learning because of the dominance of a “mainstream” focus on what instruments, participation modes, and expectations of excellence is acceptable. This can mean that for a disabled child who can not play am mainstream instrument such as a recorder, could be excluded from mainstream music education, or their access several reduced as her needs cannot be met.

There are, of course, accessible instruments that can help bridge this gap, but funding for disabled music education cannot always stretch to this. And even when it can, there is still the issue of acceptance of such an instrument in mainstream music-making: an accessible instrument can highlight difference, be difficult to train in mainstream ways.

Music-making can be a key element in music learning, when the aspects of theory, skill training, ear-to-hand coordination, creativity, self-beliefs and imagination are tested and formulated. It is an enjoyable, and playful aspect of music education and a contributor to social integration. However, segregation and difference can compound into ‘otherness’ which can further exclude disabled children.

The Research

The Digital Score PI was presented with these issues as part of an undergraduate project he was supervising at the Music department of University of Nottingham. The student - Kelvin Macharia, himself a disabled musician from Kenya - was investigating music education for disabled children in Kenya, and identified these key issues above and was seeking to understand how digital technologies might address the inclusion inbalance.

Following a survey of existing digital accessible instruments, Vear defined a wish-list of features that could be used as design considerations for an interactive digital score solution that:

- 1 was low cost to maximise availability, affordability and therefore opportunity

- 2 offered challenge and skill generation akin to learning mainstream instruments, and would be perceived on an equal, effort-earned status

- 3 had some “street cred” and of intrigue to non-disabled music students

- 4 offered a broad range of input solutions, and easily adaptable to accommodate as wide a range of accessibility as possible

- 5 embedded mainstream music theory, so that a common language was taught, perhaps even opening the system out to grades

- 6 was scalable

Vear’s solution was to build a digital score around readily available games controllers such as XBox, PlayStation. His proposition was that they were relatively low-cost (e.g. £30 for a Logitech controller online), has some “street-cred”, were pervasive in home environments that owned a games console, and were designed to usable. The advantage in an inclusive situation is that many manufacturers now supply accessible controllers (such as PlayStation’s Access), for a relatively low price (£75), with other more bespoke accessible games controllers easily built through DIY kits or bought online.

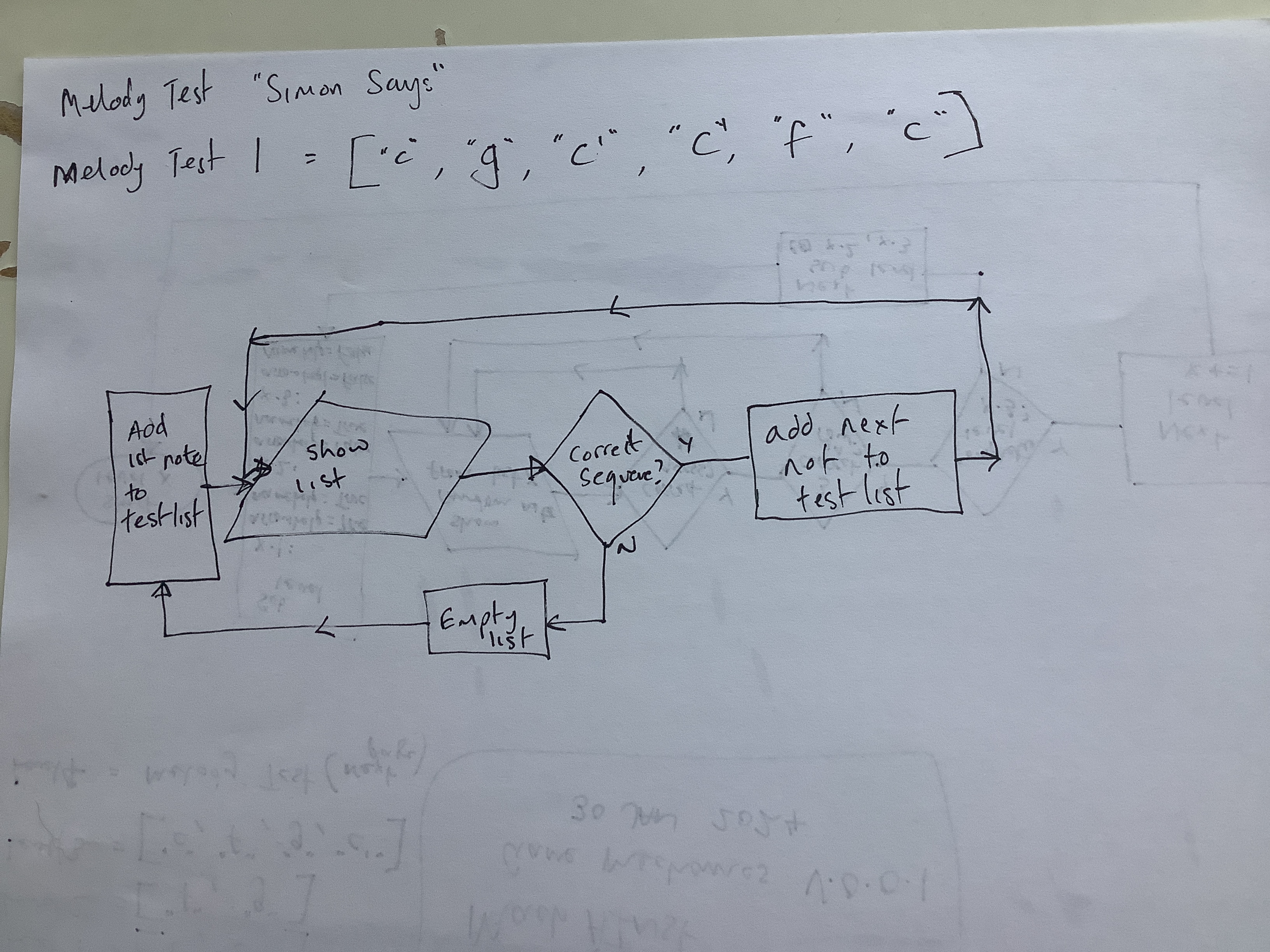

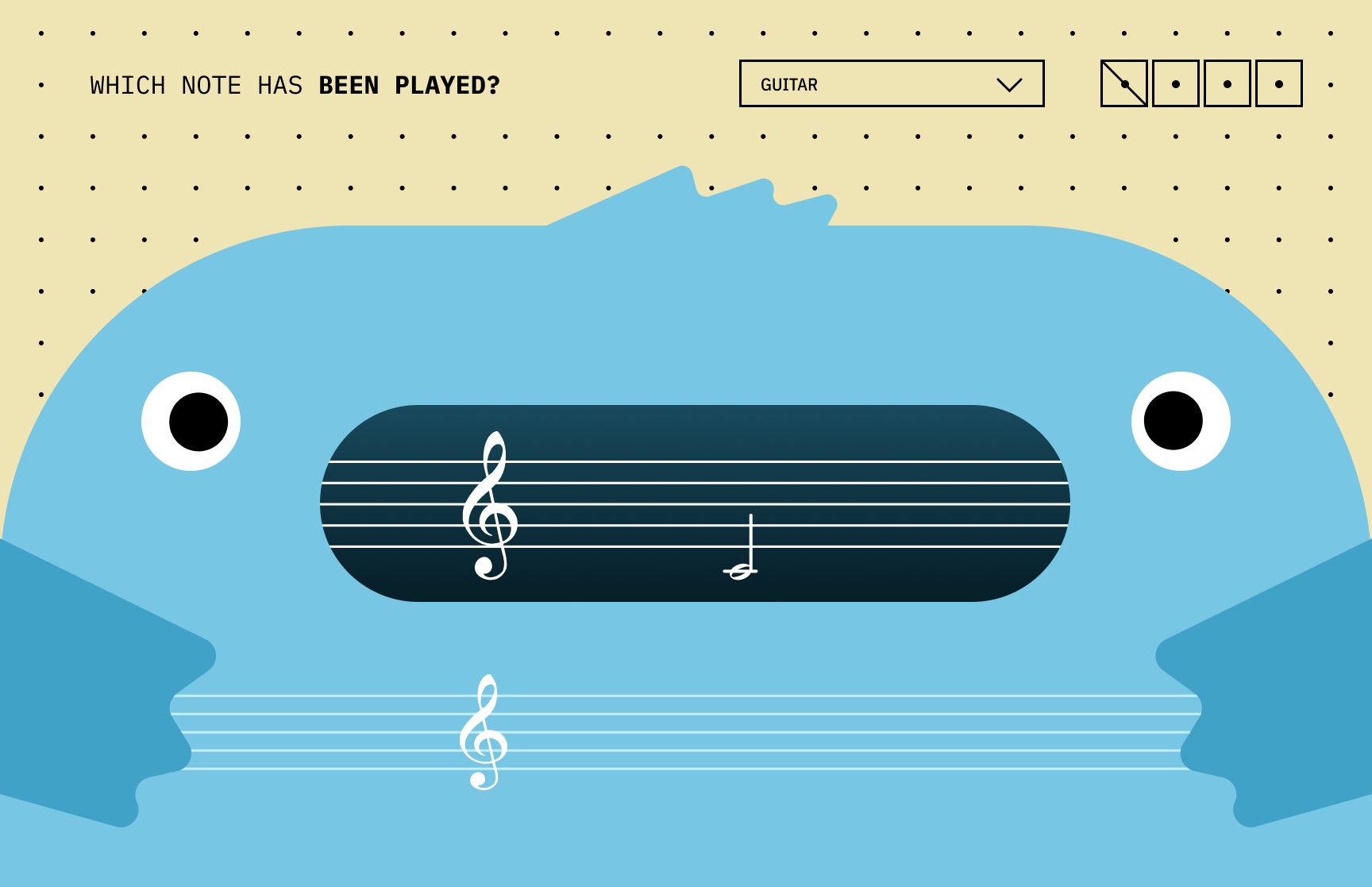

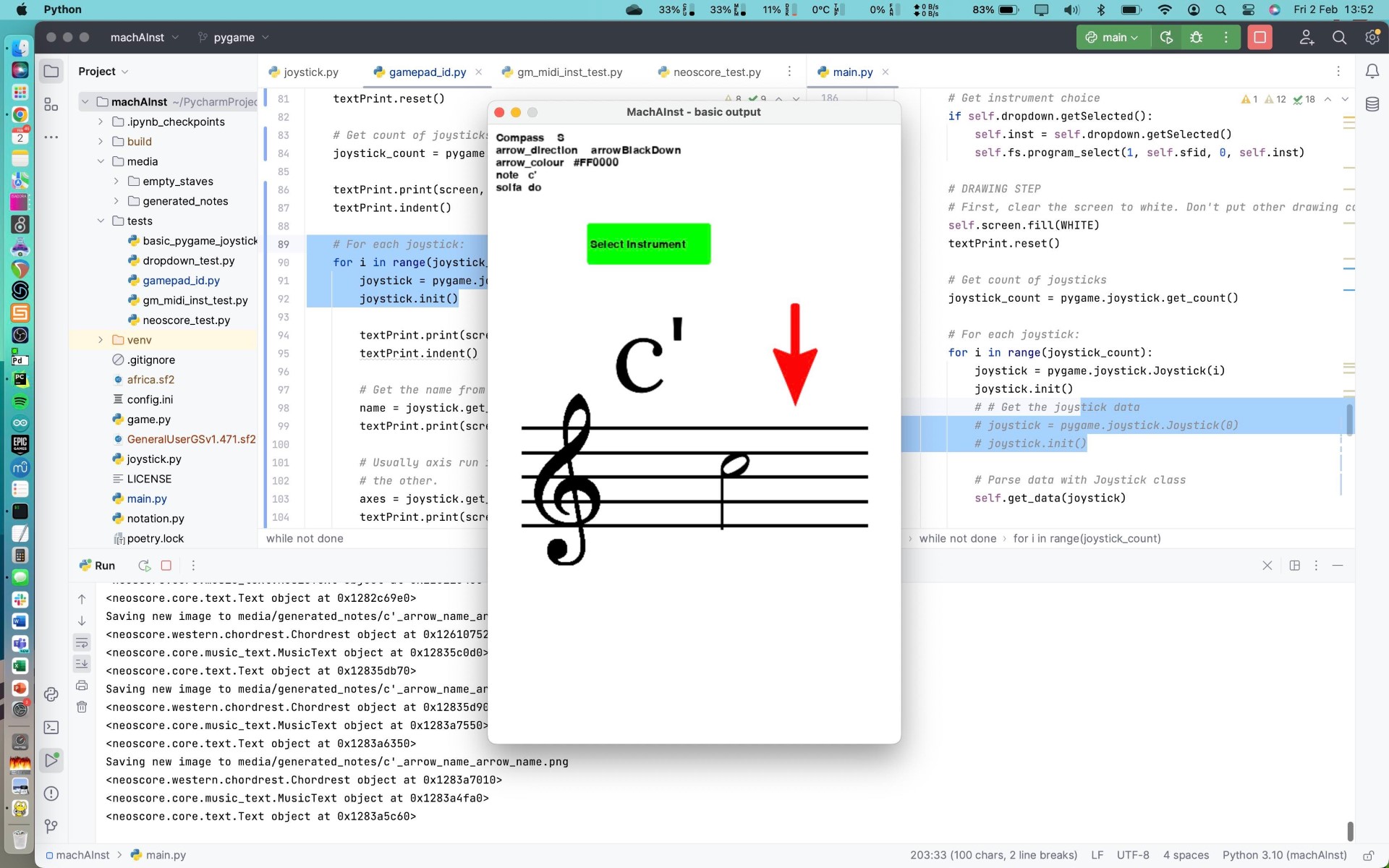

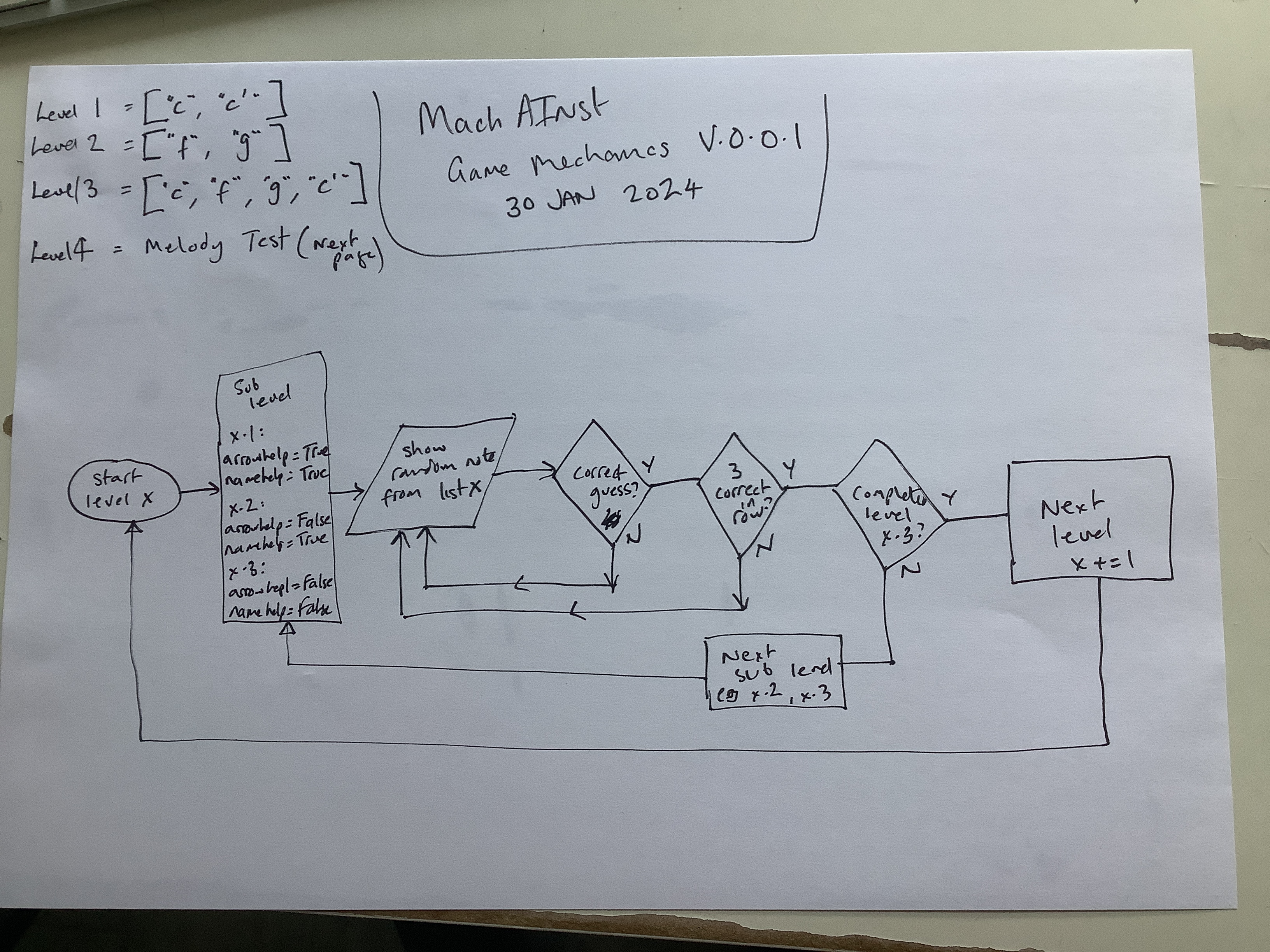

The controller alone, was only a single aspect of MachAInst with its programmed “learning game” another design aspect. MachAInst had 2 selectable modes: 1) open play, where the musician could freely play notes using the joystick and associated buttons for sharps and flats, and octave shifts, as well as volume control. There was also a selection of instruments ranging from flutes, kalimba, moog synth and vocal effects, enabling a group to be formed with different sound and parts. 2) the second mode was the “learning game” that presented a simple “follow-my-leader” game where notes were presented on the game stave (lowest in the figure above) and the musicians had to reply with that notes to move onto the next. The game was designed in levels, starting with simple octaves, and adding increasing complexity with 5ths, 3rds, and then into sharps and flats.

Because MachAInst was a digital score, the feel of the whole experience was considered in the design (see game design below. Sound effects were embedded into the user interface, as was level indicators, lives and progression comments. The design revolved around neoscore (a DigiScore project) that supported the realtime generation of the onscreen notation, and enabled various help symbols to be embedded in the score. Easy mode showed the note, with a coloured arrow (determining the joystick direction and using colours to highlight the specific notes), and also the note name, both anchored in the notation. The help symbols were removed with each correct answer, or added when mistakes were made.

The Outcomes (written by Kelvin Macharia and Craig Vear)

Macharia’s research project at SA Joytown Secondary School exceeded our hopes and expectations in several ways as MachAInst was received in an overwhelmingly positive light. Observing the complex musical activities the students could undertake with just a few goes of playing was surprising and rewarding for both Macharia, and the research participant, the music teacher at Joytown. For example, with just about an hour of playing the instrument, students could play the technical exercises required for their national exams (The Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education), such as scales and arpeggios. They also explored creating their own melodies, and set about playing various pieces in a group ensemble with singers.

The instrument also gamified the process of learning. Using the step-by-step lessons that Vear had embedded in the MachAInst “learning game”, the students felt supported to undertake these complex musical activities, capitalising on their productivity and engaged for long periods of time. As the music teacher remarked, this instrument was not like any other traditional instrument because it was also a rewarding game for the young people. The teacher went on to say it was the most engaging instrument he had seen students use, and thanks to this, some students who were previously struggling to keep engaged in class showed considerable interest in the subject, which was a surprise to the teacher. His only hope was that this interest would be sustained after the study, hence the need to continue this research and develop MachAInst further.

MachAInst presented two central answers as a solution for the access. The first one was cost-efficiency, which is a key hindrance to disabled people accessing music in Kenya, most of whom come from low-income backgrounds. With cheap and relatively accessible game controllers and a piece of software, young people were able to undertake increasingly complex musical activities. The instrument also presented easily adjustable software, which could accommodate different controllers that worked for different musicians. This is a level of customisation that is unprecedented in the Kenyan music education scene, yet a necessity for disabled musicians who have unique needs that their controller/ interfaces need to accommodate.

The other important solution that MachAInst presented to the music teacher at Joytown was its ability to combine music theory and practical musicianship into one. Our research shows that combining music theory and the act of music-making is a significant challenge for many secondary school students in Kenya. This was also the case for the students at Joytown, as the music teacher revealed. In his long teaching career, he was used to having students who could write the music but had challenges performing it, or vice versa. However, MachAInst combined elements of sightreading, aural musicianship, hand-ear coordination and performance into one. The musicians could see the note they were playing, hear it and perform it simultaneously, which, as the teacher observes, goes a long way in creating holistic musicians who can hear, read and perform music.

While this was intended to solve the challenges that disabled people face in music education, particularly a largely unaccommodating education system and the high cost of acquiring traditional instruments and virtually unaffordable adapted instruments, it solves problems that are not unique to disabled musicians. Consequently, the music teacher at Joytown sees it as the future of music education in Kenya.

Code

- The GitHub repository for this code LINK

Participants

Kelvin Macharia Macharia is a disabled musician from Kenya, currently studying for a BA(Hons) in Music at the University of Nottingham. His final year research project investigated how digital technologies can mitigate the barriers that hinder young disabled people from accessing music education in Kenya. MachAInst was designed by Vear to offer a cost-effective and music-theory embedded solution for Macharia to trial in his research project.

Mr Benjamin Kareh Joytown music teacher who was the main participant for Macharia’s research, and offered valuable feedback for the design of the score/ instrument, and conducted valuable qualitative and quantitative surveys with his students.

Research Team

Dr Fabrizio Poltronieri MachAInst User-Interface.

Jonattas Poltronieri Graphic Design. Website

Partners

SA Joytown Secondary School

Joytown is a co-educational boarding primary and secondary school for learners with physical disabilities in

Thika town, Kiambu County, Kenya